The Change of Art World in North America After Trump

50 ast February, Trick News commentator Sean Hannity challenged his detractors to criticise a portrait ofDonald Trump painted past the arch-conservative artist Jon McNaughton. "The 'left,'" Hannity wrote on Twitter, "loves fine art, and especially taxpayer funded fine art that is 'provocative.'" He wanted to see if that love of art would extend to McNaughton's portrait, in which a characteristically navy-suited Trump, bearing a presumably unintentional resemblance to Newt Gingrich, clutches a tattered American flag as he stands in the middle of a stadium full of football fans. The piece is titled Respect the Flag, invoking protests against racial injustice that several NFL players have staged during the national anthem.

Hannity'south willingness to cede "fine art" to the "left" was a natural extension of the civilisation wars waged by the president, which have turned the most American social phenomena – football, TV sitcoms, ESPN and fifty-fifty department stores – into partisan battlegrounds. Lost, however, in the whirlpool of clamour and anarchy that is the Trump administration, is the president and his party's indifference toward the arts – both as a publicly funded entity and a platform for American values.

Last week, Artsy reported that the US Department of State has yet to select an American artist to represent the land at the 2019 Venice Biennale, which opens in May. Typically, countries denote their representatives at least a twelvemonth in advance and so the artists take time to make new work for what is widely considered the world's pre-eminent international art exhibition. There is something specially germane nearly this twelvemonth'due south theme, too: titled May You Live in Interesting Times, the exhibition will include "artworks that reflect upon precarious aspects of existence today, including different threats to primal traditions, institutions and relationships of the postwar club", curator Ralph Rugoff explained.

By US selections, including Mark Bradford, Joan Jonas and Sarah Sze, were announced at least a full twelvemonth before the biennale. At present, with that deadline passed, country department staffers and art cognoscenti doubtable an explicitly pro-Trump artist – like McNaughton, or peradventure Scott LoBaido, the self-titled "patriot creative person" from Staten Isle best known for his 16ft starred-and-striped T statue – will make the grade. Some, including Cocked reporter Nate Freeman, wonder if anyone will be selected at all, in keeping with a president whose shown a philistine condone for the arts and international engagement.

Photograph: David Levene/The Guardian

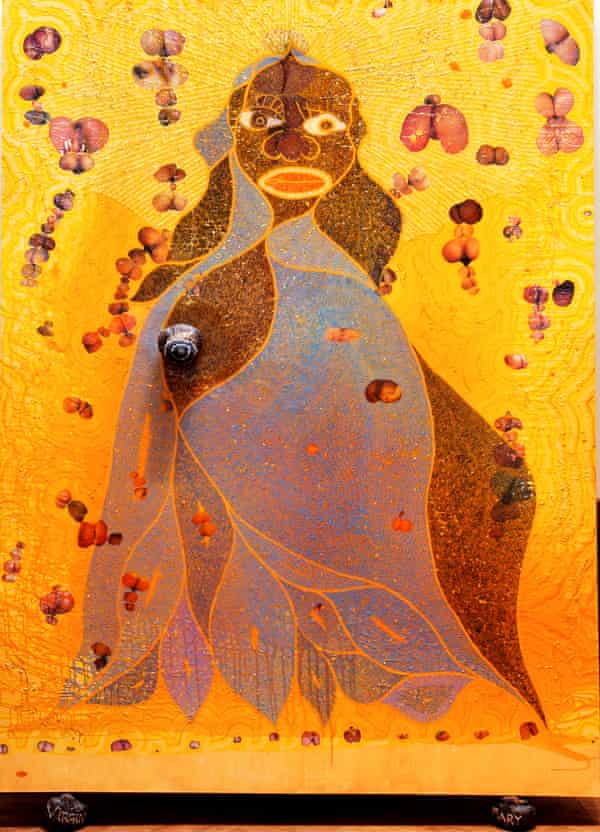

"Trump seems utterly confused in even defining the word civilization," says Virginia Shore, sometime master curator of the country department's Art in Embassies plan, which since 1963 has commissioned United states of america fine art for foreign embassies and consulates every bit a means of cross-cultural diplomacy. "I wish the president would spend fourth dimension in a museum or gallery and larn the true meaning of culture." For a human who'due south lived nigh of his life in New York City, Trump has non been especially involved in its arable arts scene. On Wagner'southward Ring Cycle he said: "Never again." On Chris Ofili's The Holy Virgin Mary, which then mayor Rudy Giuliani tried to ban: "Absolutely gross, degenerate stuff." Even the legitimacy of Trump's Renoir was debunked when the Fine art Constitute of Chicago said the original hangs in its gallery.

The notion that the Us delegate for what is known as the "Olympics of fine art" would be contingent on their fidelity to the president is, to many, in diametric opposition to the spirit of the biennale, which serves as a kind of visual expression of a country'south values, a platform for its "best and brightest," as Christopher Bedford says. Bedford, who curated Bradford's exhibit at the 2017 biennale, thought of "liberty, equity and justice for all" every bit he championed Bradford's submission. Trump, on the other hand, has made no secret of his disfavor to government-funded arts, "liberal Hollywood" and, by extension, the mostly anti-Trump arts customs.

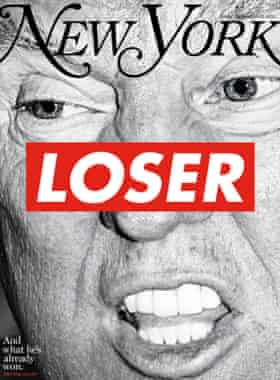

That community, as it is wont to practise in moments of political unrest, has responded in kind. At that place was Barbara Kruger's 2016 cover of New York magazine, in which the word "loser" – a favourite epithet of the president – graces a particularly unflattering close-up photo of him. Other highlights include Judith Bernstein's Money Shot – Blue Balls, in which Trump appears abreast phallic imagery and the word "Trumpenschlong," and Awol Erizku's series Make America Great Again, in which the keepsake of revolutionary black power group the Black Panthers is printed on peak of icons including the U.s. flag. By August of Trump's get-go yr in office, all 16 artists, authors and architects on the President'south Commission on the Arts and the Humanities resigned in opposition to Trump's equivocations after the neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville. A White House spokeswoman responded that the president planned to disband the commission anyhow.

When the White House requested a Van Gogh painting from the Guggenheim for the president'due south living quarters, the museum rebuffed them and offered a solid 18-carat-gilt toilet by the artist Maurizio Cattelan instead. And Trump, in his 2018 and 2019 budget plans, proposed eliminating funding the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), making him the showtime president to publicly propose doing so since the agencies were established in 1965. Ultimately, Congress would pass a spending bill that saw a pocket-sized $3m funding increase for both endowments.

While the Trump presidency may mark an escalation in tensions between the art world and the federal regime, it is inappreciably the beginning such bust-upward. Even though the NEA and NEH make up about one 10th of 1% of the almanac federal budget, efforts to siphon those funds away from the arts have ebbed and flowed since the 1980s.

Ronald Reagan, on taking office in 1981, planned to kill the onetime endowment altogether but was inhibited when a special task force lobbied him on the agency's behalf. A decade later on, in response to a scathing Time magazine commodity by art critic Robert Hughes, in which he called rightwing attempts to decimate the NEA "cultural confusion", former speaker of the business firm Newt Gingrich slammed the NEA, NEH and Corporation for Public Broadcasting as pet programmes, not sacred cows. Some government subsidised artworks, Gingrich wrote, "are clearly designed to undermine our civilization", a reference to Andres Serrano's Piss Christ, a 1987 photograph, funded with NEA money, depicting a xiii-inch plastic crucifix dunked in urine.

The image is often invoked equally a political cudgel in the civilization wars, understood past hardline conservatives as proof of a need for the separation of art and state. In a 2017 polemic against taxpayer-funded art, it took the Pulitzer-winning conservative journalist George Will all of two sentences to refer to Piss Christ as "rubbish". And twenty years before, bourgeois think tank the Heritage Foundation inveighed against the NEA "welfare for cultural elitists" tainted by "a radical virus of multiculturalism", a charge that reads today as a dog-whistle to the Americans who helped elect Trump. That the bureau funds art therapy for military personnel – too as projects in every congressional district in the country – many of which are community based and would stop to office without NEA funding – is artfully omitted from arguments against its existence.

"There is a perception among those who are maybe somewhat correct-leaning that the art globe is such a monetized sphere that it could fund itself privately rather than existence, in any sense, state-supported," says Bedford, now director of the Baltimore Museum of Art. Merely art, he says, "is every bit vital and indispensable as mental health care, wellness intendance, or instruction. As such, at that place should exist a government investment in providing not only advocacy for the arts but access for all."

Trump, though, is governed by political expedience. And as a effect, he has successfully managed to sow discord where information technology benefits him – and angers his base – virtually: national anthem protests; transgender bathrooms and military service; Roseanne; Nordstrom pulling his girl's wearable line; safe spaces and trigger warnings … the list of petty grievances weaponised as electoral ammo goes on.

It'due south foreseeable, then, that the Venice Biennale, funded in part by the state department, becomes another forepart in the civilisation wars, giving the president a take chances to stick it to a community his backers consider frivolous and highbrow. Mayhap more likely, though, is continued detachment. Eighteen months in, the assistants has nevertheless to award whatever national medals of arts or humanities, a White House tradition that dates back to the 1980s. It has, still, awarded medals for military service and law enforcement, a pattern that suggests Trump adheres to presidential orthodoxy only if it shores up his base.

Past Trump's ain design, and Hannity's account, art is just another wedge between that base and the left, a sensibility that can exist used to convince groups of Americans they're irrevocably different from one some other. Hannity'south tweet was eventually turned into a popular meme that, using images of Jeff Goldblum as a centaur or a pregnant SpongeBob, mocked the idea of art as a partisan activity. But in a country as immersed in cultural strife as it was during the top of Reagan-era culture wars, it may well go 1. And an event as distinguished as the Venice Biennale may not be spared.

osbornewittaloo74.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/jul/30/how-the-art-world-got-embroiled-in-trump-culture-war-venice-biennaletrump-v-the-art-world-from-a-gold-toilet-to-an-empty-venice-pavilion

0 Response to "The Change of Art World in North America After Trump"

Post a Comment